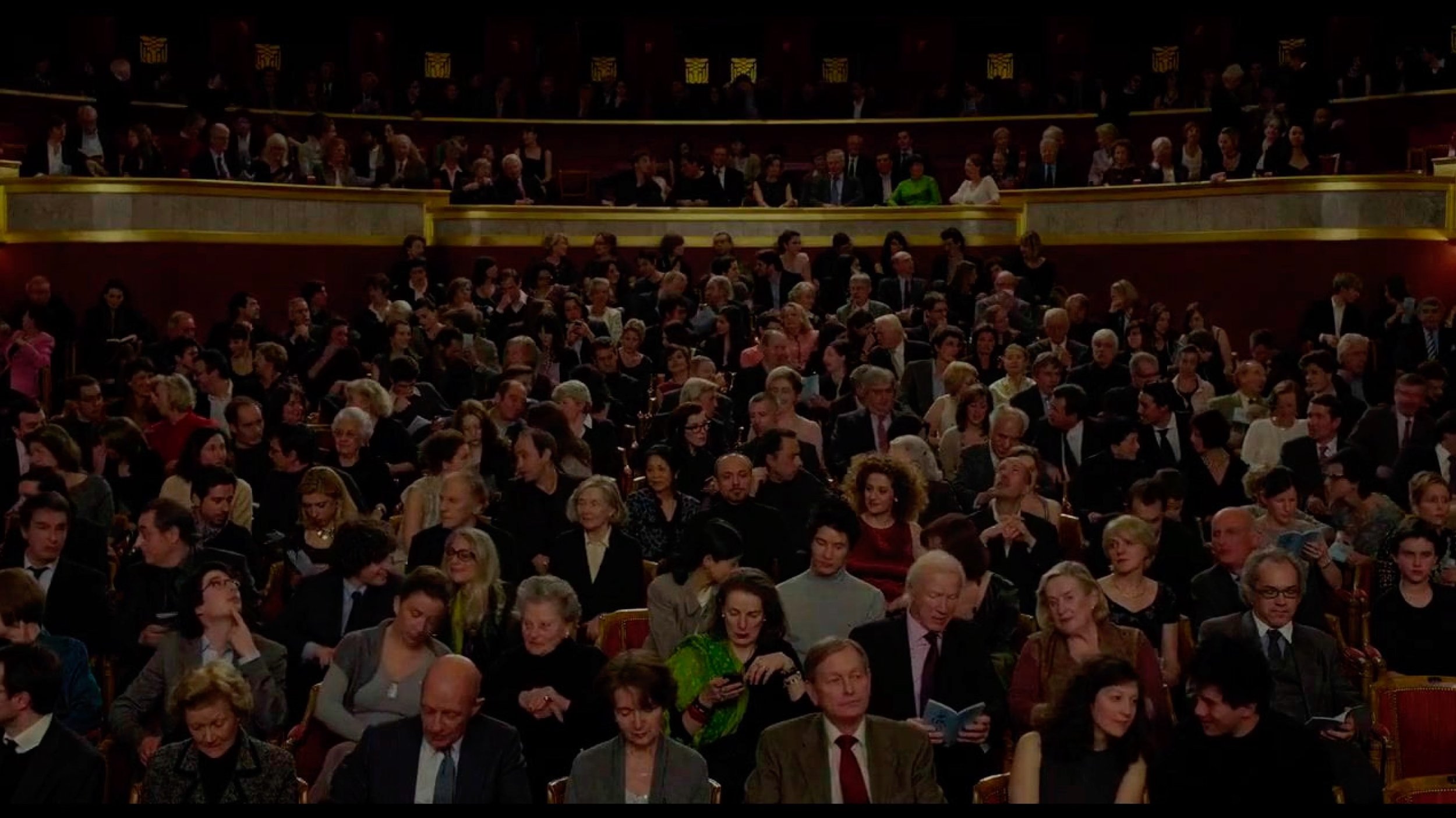

In a recent conversation Ukrainian filmmaker Sergei Loznitsa considers the shared social experience of the cinema space:

“Now we have many different opportunities – TV, streaming services, websites, depending on what you like. It’s different though, because you watch films alone. You don’t feel the way the audience is receiving the film. I’m a little afraid of that, because I always make films for big screens with a good 5.1 sound and I like to feel the emotions of the viewers. Watching films together triggers immediate discussions afterwards. On the other hand, when you watch films alone or just with very few people, you have very limited possibilities to talk and to listen to what others have to say. In the future, cinemas may be like opera houses – something very special and unique. That’s why festivals are so crucial. They have to keep that possibility of watching films on a big screen. “

In a cultural landscape engineered to satisfy consumer demand, it is easy to feel that nothing in the world shows up as having any more value than anything else. All is simply a matter of choice according to the prevailing mood of any given moment. The apparent ‘levelling’ of meaning that pervades our culture expresses itself, in part, as the never-ending, accelerated consumption of private, portable and disposable media content. This is the raison d'etre of todays Content Industry.

Writing in the 1980s, Albert Borgmann presents a philosphy of focus things and practices to re-examine the instrumental rationality of our technological living. He writes:

"A focus gathers the relations of its context and radiates into its surroundings and informs them".

One of the examples Borgmann uses is the “culture of the table”; the table that gathers together the active participation of the family, its traditions, cultures and the gits of nature.

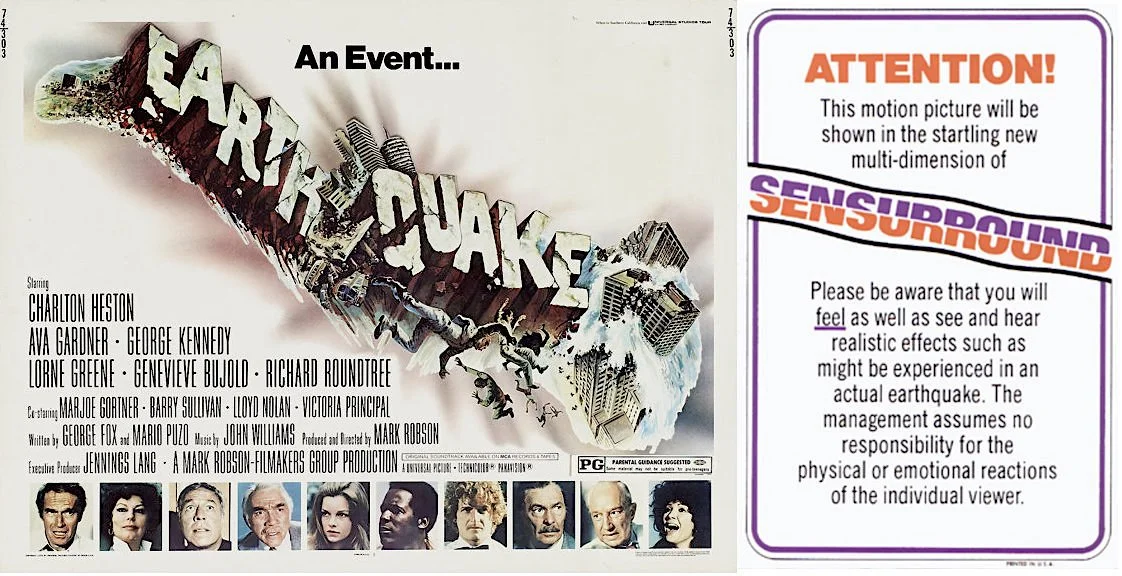

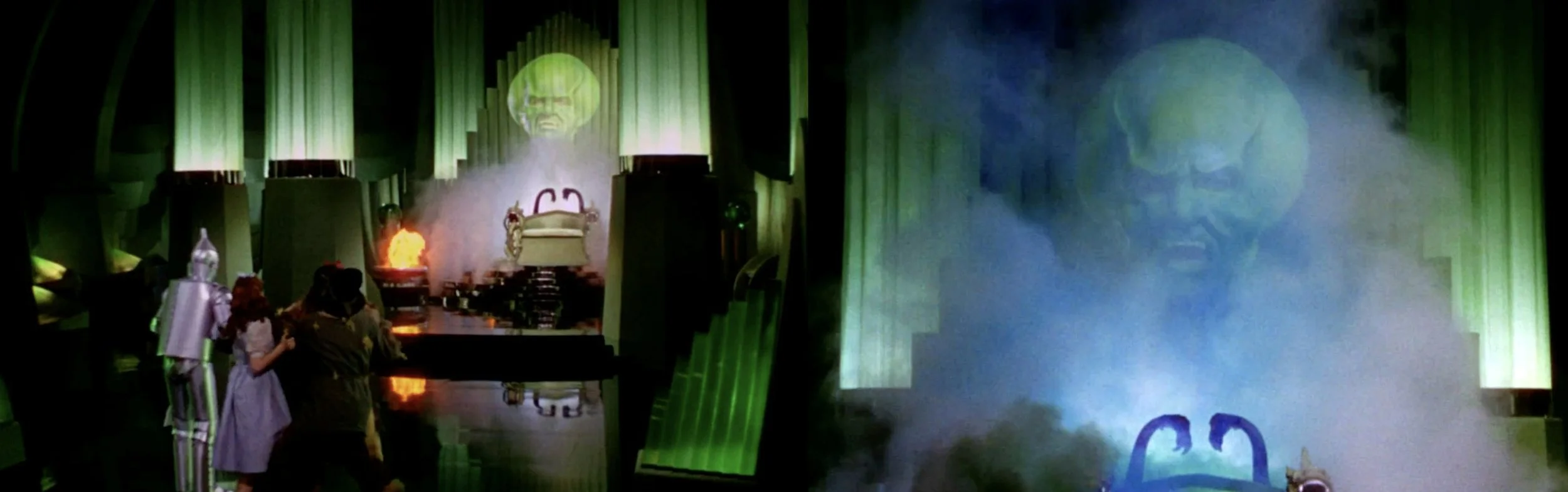

The cinema is a publicly accessible place for the coordination of a focal event - a unique kind of viewing and listening space. A site for shared and private performance spectatorship, “a paradoxical mass-intimacy” as Walter Murch describes it. It gathers the scattered people around the glow of its screen, bringing into focus our private and shared condition.

Inside spectators submit themselves to the uninterrupted flow of time that constitutes the film performance. This collective experience, as with all socially sanctioned rituals, manifests the spectator’s shared ‘horizon of significance’; that which shows up in the world at that moment as significant and meaningful.