In December 1970, the first Invisible Cinema opened in New York at the original Anthology Film Archives. It ran till 1974. It was designed by Austrian filmmaker Peter Kubelka as a distraction-free, total cinematic environment.

The Invisible Cinema was envisaged as an architectural space that would be completely focused on the image and sound of the film.

"All the elements of the cinema are black: the rugs, the seats, the walls, the ceiling. Seat hoods and the elevation of the rows protect one's view of the screen from interception by the heads of viewers in front. Blinders eliminate the possibility of distractions from the side. We call it The Invisible Cinema." (Manifesto quoted from Karsten Witte's collection Theorie des Kinos).

Later in 1989 after a modified version of the original idea was set up in the film auditorium of the Albertina in Vienna, author and critic Harry Tomicek wrote:

“The conversion of the auditorium makes the 'Invisible Cinema' the only cinema in the world to remain shadowed to the point of invisibility and utterly removed from our perception while we see films. Similarly, in remaining invisible, this architectural space grants us a maximum of concentration and pleasurable immersion in what becomes visible and audible within it: a suggested world made of image and sound known as film." (Neue Zürcher Zeitung)

In the article Invisible Cinema, A Movie Viewing Machine, author Gamze Yesildag writes how Peter Kubelka envisioned the cinema:

“He calls the space he designed a ‘movie-viewing machine’: This revolutionary and controversial design is based on the idea of cameras, movie processing machines, film editing machines and projectors to which the film is attached. The room where the movie is watched must be a machine designed for watching movies.”

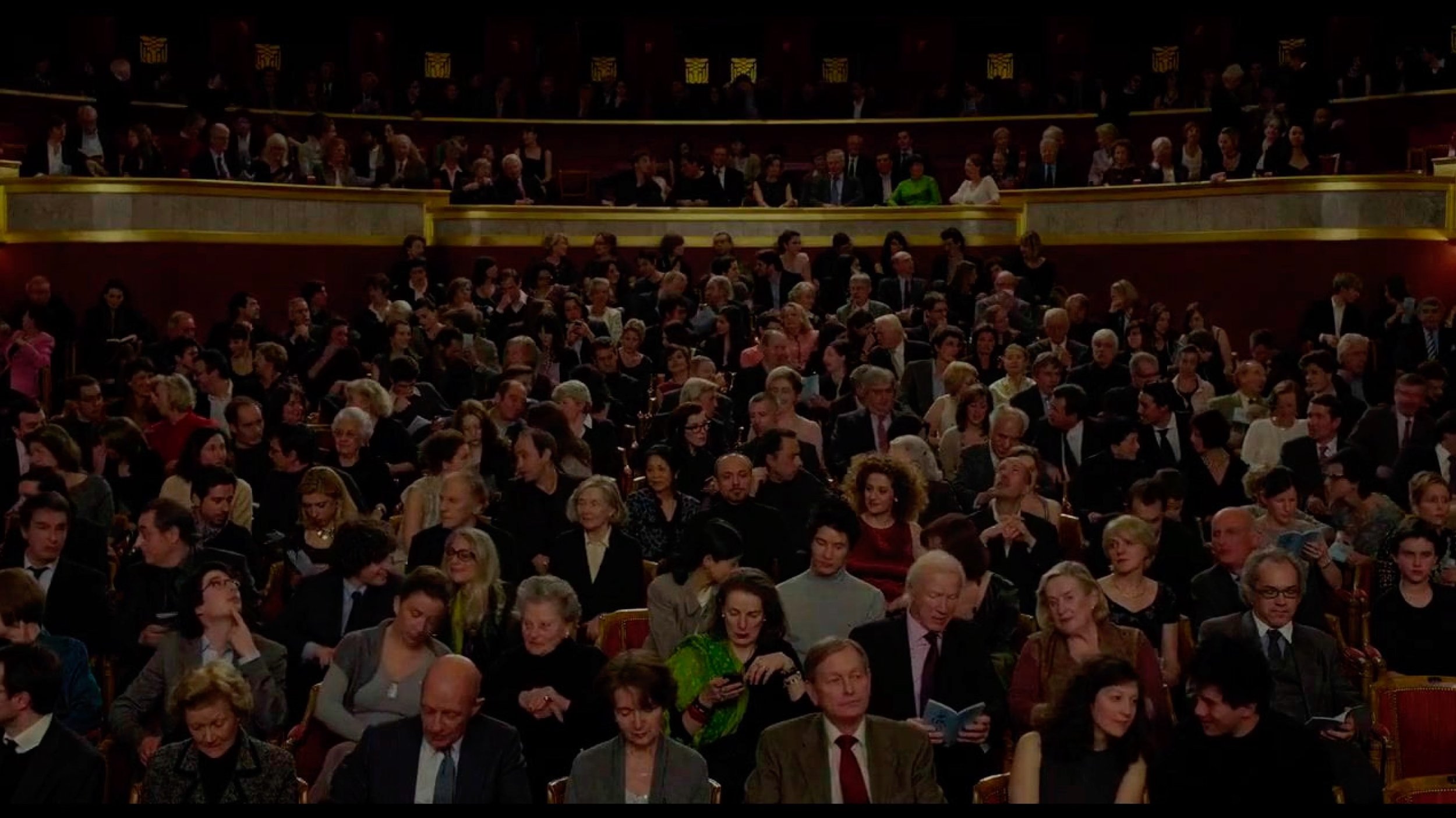

Image Source: Invisible Cinema, A Movie Viewing Machine