The cinema developed out of the theatre and concert hall. All share an interest in the eye.

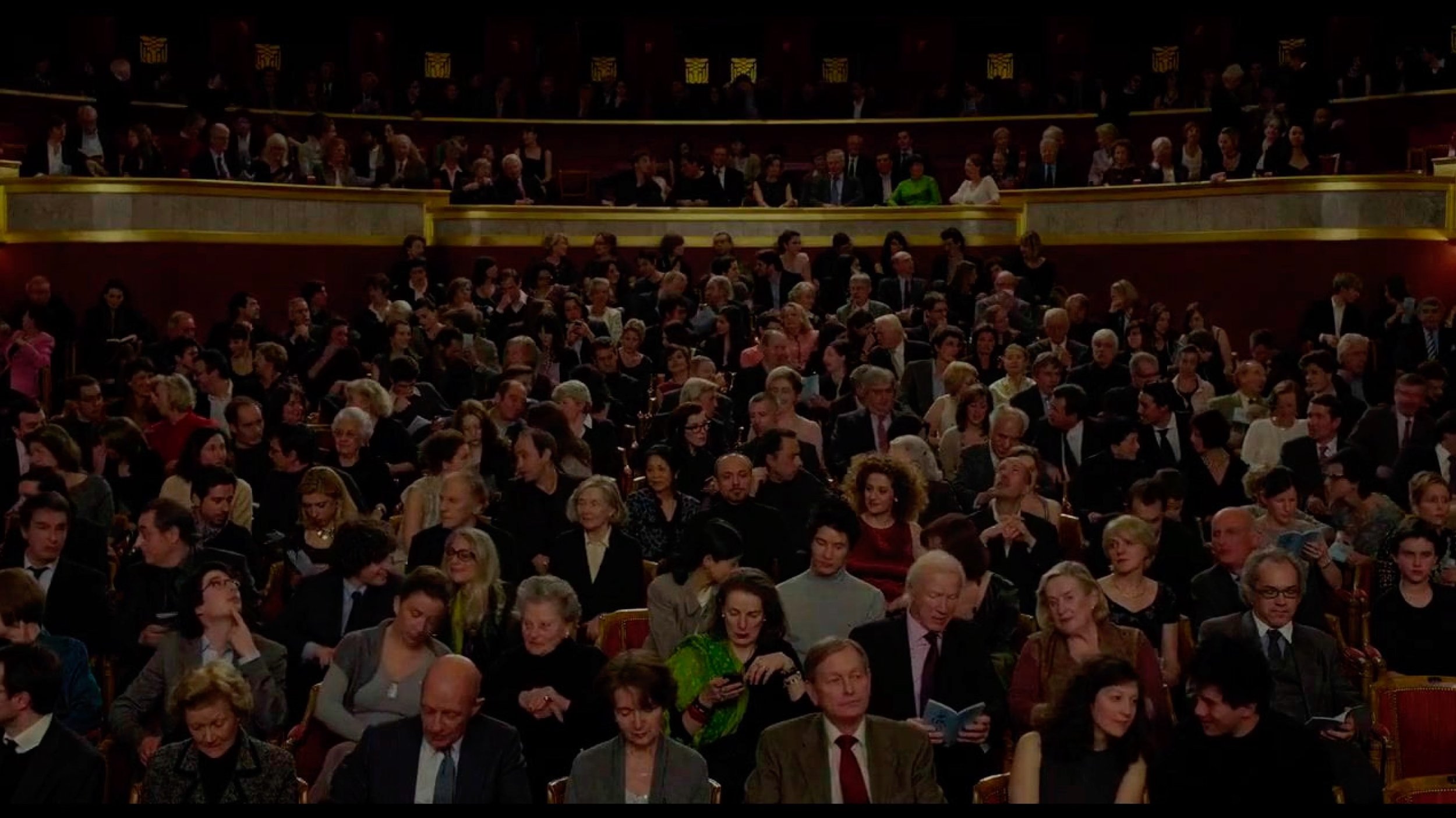

Today, in most parts of the world, the typical Euro-centric concert hall, theatre or cinema space politely requests its visitors to be silent and still for the duration of the programme. This is in order to minimise distractions and create a suitable atmosphere for concentrated attention.

Amour [2012] dir. Michael Haneke

The conventions of cinema spectatorship originate in the 19th Century. This was a time when attitudes concerning the proper conduct and social behaviour at classical music concerts began to change. Audience participation, background talking and the presence of animals inside performance venues began to be outlawed. Instead, a quieter more reverential atmosphere began to emerge that cultivated the private and polite contemplation of the performance spectacle.

Contemporary, westernised film spectatorship is an expression of a 20th century modernist value system. This promotes certain attitudes of decorum towards the veneration of high art. Such values serve to affirm an atmosphere of disciplined spectatorship. In music, the still, silent, concentrated listener, that cultivates, according to Theodor Adorno, the authentic, actively engaged expert listener. This is in contrast to the common listener, the jitterbug, who is slavishly subsumed by the salacious rhythms of popular music.

For Adorno high art and intellectualism are pitted against the entertainment and commercialisation of the emerging 20th Century Culture Industry; the mind at war with the body. But this disciplined spectatorship is only one among many ways of experiencing performance events.

In a typical all-night Javanese shadow puppet performance (Wayang Kulit) the audience is welcome to come and go as they please, engaging with the puppets and music in different ways from different perspectives. Spectators are free to seat themselves either side of the translucent screen. On one side they can witness the play of shadows. On the other they can watch the master pupeteer (Dalang) manipulate the various hand-made puppets while also observing the gamelan musicians performing along side him. Food stalls are often setup nearby, and the general ebb and flow of village activity mingles with the sounds of the gamelan and the flickering display of shadows.

Throughout Indonesia performance of all kinds feel like an occasion to strengthen community bonds and identity. These collective rituals assist in establishing and maintaining healthy relationships with the spirit world. Ethnomusicologists and anthropologists find similar ritualised patterns of behaviour and meaning-forming occuring in other cultures and communities throughout the world.

Musicologist Christopher Small expresses these ideas ecologically through his concept of Musicking.

"The act of musicking establishes in the place where it is happening a set of relationships, and it is in those relationships that the meaning of the act lies. They are to be found not only between those organized sounds which are conventionally thought of as being the stuff of musical meaning but also between the people who are taking part, in whatever capacity, in the performance; and they model, or stand as metaphor for, ideal relationships as the participants in the performance imagine them to be: relationships between person and person, between individual and society, between humanity and the natural world and even perhaps the supernatural world." [Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening, 1998]

As Small describes in his book, Musicking can be applied to performance practices across all cultures and traditions. This includes all amatuer as well as professional forms of the European classical tradition.

What kind of relationships are established in the cinema space? Is Musicking part of the film viewing/listening experience?