The cinema is a uniquely immersive space. It sensorially envelops the spectator with sound and light. Through submission the audience comports itself as active spectators.

Images and sounds projected into cinema space stand over and above the spectator, both temporally and spatially. The spectator remains small, the cinema machine big. Private, mobile technology inverts this relationship.

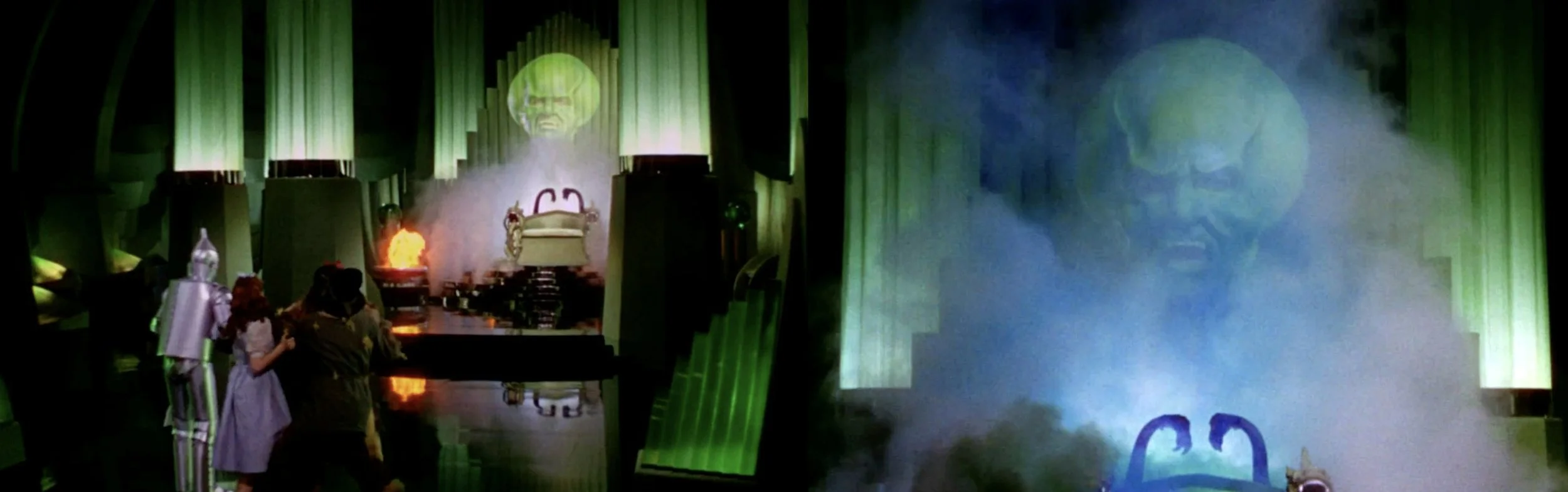

Wizard of Oz [1939] dir. Victor Fleming

Media archaeologist Erkki Huhtamo has written about the “Gulliverisation of the world”. Marked by accelerated industrial production, mass urbanisation, developments in advertising and technological innovation, this “increasing and diminishing of perspectives” began to emerge in the second half of the 19th century and continued into the early part of the 20th century. It led to what Huhtamo describes as a:

“radical change in the anthropomorphic, human-sized based world of perception of Western man […] the big became even bigger and the small even smaller.” [During this period'] “the size of the human observer kept on shifting between gigantic (in relation to the carte-de-visite photographs ortradecards) and Lilliputhian (in front of large billboards or below advertising spectacles in the sky). Something similar happened in the field of media 'immersion' into an enormous circular panorama or diorama painting (and later, the cinema screen) [that] found its counterpart in the act of peeking at three-dimensional photographs with the ubiquitous hand-held stereoscope.”

The big screen and the small screen - the big room and the little room. Differences in scale distinguish a public form of spectatorship from a domestic one. Through these differences of scale, territory and accessibility, the public space (cinema) - a site for possible social encounters - always threatens a potential diminishing of individual autonomy. The challenge to modern urban living is, as Georg Simmel outlined in 1903:

“the attempt of the individual to maintain the independence and individuality of his existence against the sovereign powers of society, against the weight of the historical heritage and the external culture and technique of life.”

To leave the house is to relinquish absolute autonomy. In contrast, the domestic setting of the home (television) promises a sanctuary of individual control and comfort. Huhtamo writes:

“Gulliverisation operates at the divide between the public and the private. The urban environment, with the skyscraper as its ultimate manifestation, became more and more 'inhuman', whereas the home provided a return to the anthropomorphic scale.”

Reference: Gulliver in Figurine Land (en) [1990] E. Huhtamo, Messages on the Wall: An Archaeology of Public Media Displays [2009] E. Huhtamo, The Metropolis and Mental Life [1903] G. Simmel